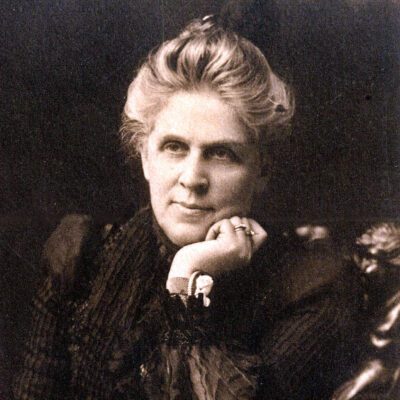

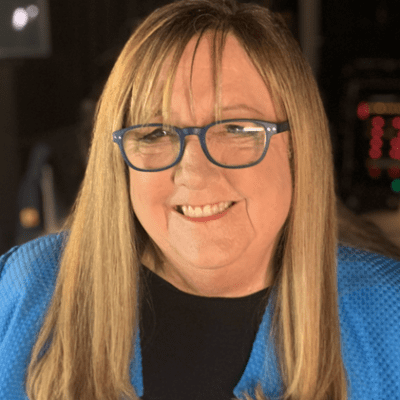

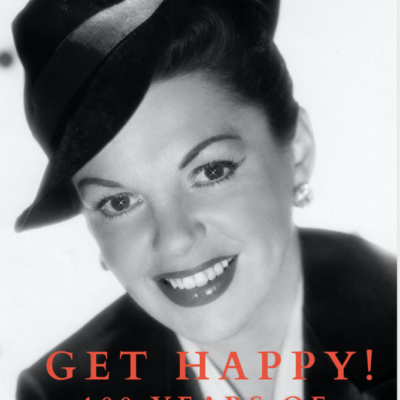

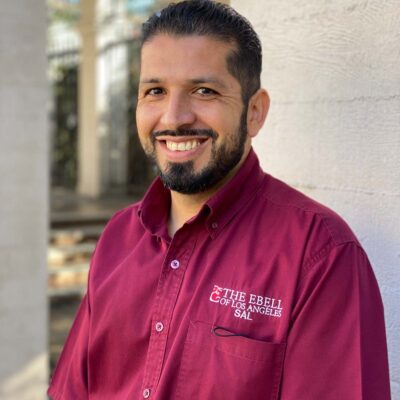

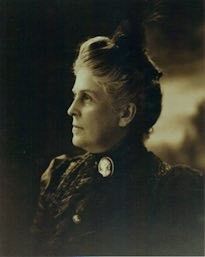

Another view of our founder Harriet Russell Strong

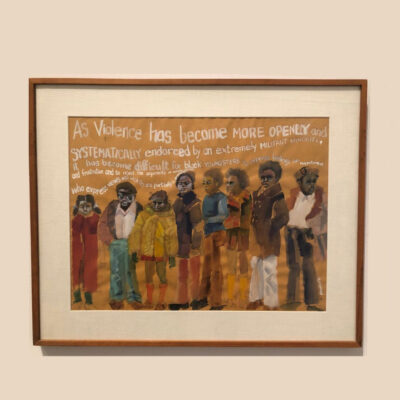

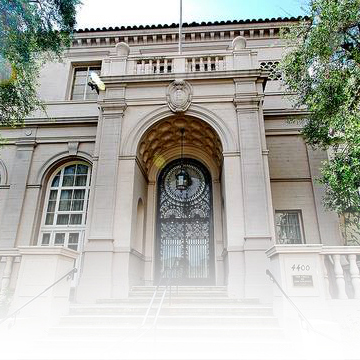

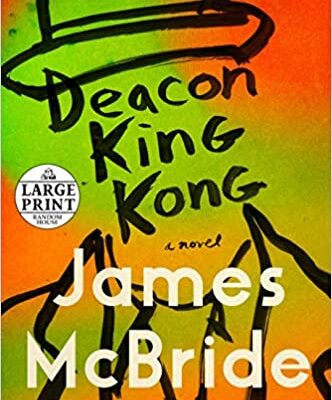

As Charter Day approaches, the annual day we honor our Ebell foremothers, let’s look back on our principal founder, Harriet Russell Strong. You know her by her portrait that hangs permanently on the east wall of the Art Salon. She looms large, her somewhat stern countenance seemingly the picture of a privileged woman.

You are in for a big surprise. Harriet was born in 1844. She would have seen the Gold Rush era, lived through the Civil War, and ushered in the Victorian age. Yet, you will not only find her more inspiring than you can possibly imagine, and totally relatable today. For example, Harriet knew a thing or two about water conservation and drought, how to succeed as a single mom, how to make do on a shoestring budget, what to do to champion women’s rights and even how to endure a punishing commute. I am not sure of the origin of our Ebell motto, I Will Find a Way or Make One, but it seems as if it was Harriet’s personal story and legacy to pass on.

Founding The Ebell at age 50, and serving three terms as president, was only one of her many accomplishments, one more extraordinary than the next. But to really appreciate her successes, let’s look at the seemingly insurmountable challenges she faced.

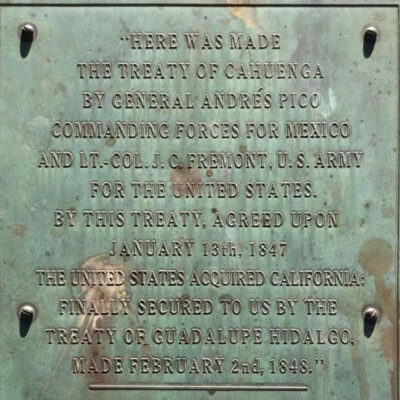

She and her husband Charles Strong lived in Northern California, and for a while in Carson City, Nevada, and had four daughters. Charles had a lucrative career in banking, publishing and then mining, amassing a fortune. Then things took a downward spiral and for his business and health reasons they moved to the San Gabriel Valley where Charles decided to try his hand at farming. They had befriended the famous last Mexican governor of California, Senor Pio Pico, and purchased 325 acres of ranch land from him in Whittier. It had been used for wheat farming, and they named it Rancho del Fuerte. If you know Spanish, you know that translates to strong.

Apparently, Charles didn’t warm to farming life, and his problems worsened. They turned very sour when he became the victim of a swindle and, without confiding in his wife, he plunged the ranch into debt. It gets worse. He then took his own life.

So here is Harriet at age 39 with four daughters, a mountain of debt, and a ranch without any viable water source. She made a bold decision, and abandoned wheat to plant a grove of walnut trees. It would be a far more lucrative crop, but walnut trees had never been grown in this part of the country. Walnuts required lots of water, and there was no irrigation.

This is where Harriet’s inventing career begins, one that would make her a legend in her own time through to today. With no engineering background, she created her own dry farming technique by digging artesian wells and setting up a series of multiple dams –then expanding the property to accommodate a pumping system. It all worked, and she was smart enough to obtain a patent on the process. She was soon a star and became known as the “Walnut Queen” – the leading commercial walnut producer in the nation. Word got around. She made a name for herself in Washington D.C. in connection with the Colorado River water usage, and– ta da! —the technology used in the creation of the Hoover Dam! By the way, she was out of debt and saved her family within five years.

In today’s world she once was dubbed “The bad ass woman of farming.” In 1893 it earned her two medals at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. She subsequently became a member of the National Women’s Hall of Fame, and quite recently was inducted into the Inventor’s Hall of Fame, all for her work with water and its conservation. That’s our Harriet.

As a side note to the farming story, she planted a secondary crop between the rows of walnut trees that would bring income while waiting for the trees to mature—pampas grass. Pampas had various uses of value at the time, but it was about to become fashionable as a substitute for feathers in women’s millinery, thereby saving the wellbeing of the bird population that had become the victims of the style conscious.

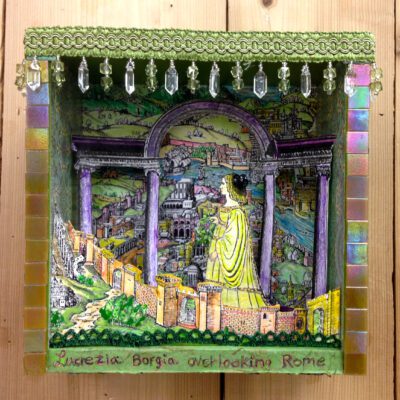

Not only a conservationist, but she was also a preservationist. In the same year that our club was founded, her friend Pio Pico died. Harriet took it upon herself to see that his adobe mansion was preserved. It had quickly fallen into disrepair and by 1906 she stepped in to save it, and its history, and it survives today thanks to her efforts.

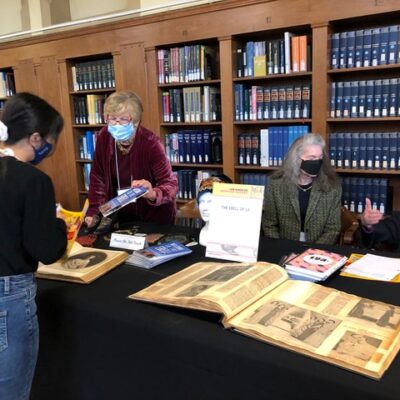

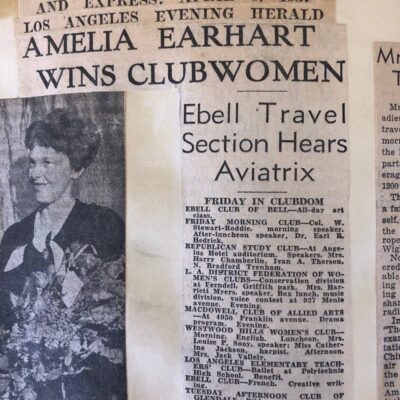

Impressed yet? There is more. Harriet was active in other arts and women’s organizations in Los Angeles. She was a member of the Friday Morning Club, the Ruskin Art Club. Passionate about arts and culture, she was a musical composer in her own right, having published a number of songs and a book of musical sketches (that we are on the lookout for to add to our Ebell archives.) She also served as Vice President of the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra Association.

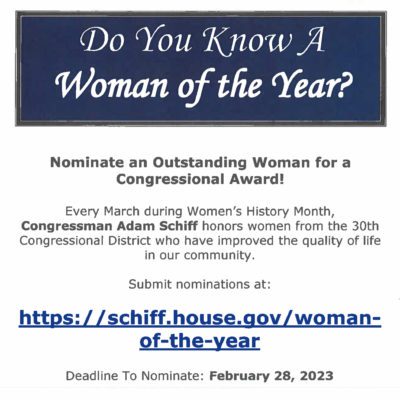

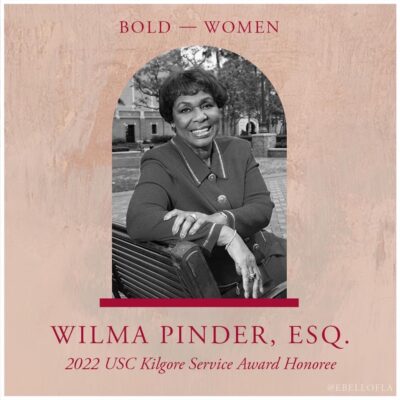

We know of five patents she registered, not just one. Not all are about dam reservoirs, water storage and impounding debris. She had a patent for window sashes, a window raise-and-lower device and even a hook-and-eye fastener. She was the first female trustee of the University of Southern California Law School, and the first female member of the Board of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. She traveled across the country with Susan B. Anthony to promote women’s causes. As we know well, she was a proponent of women’s education, since The Ebell was founded for that primary purpose!

Summing her up, Harriet was an inventor, a business owner, a suffragist, a conservationist, a philanthropist and a mom. But her place in history as a female pioneer of water sciences and women’s rights has inspired many to find solutions to today’s climate issues and so much more.

Her remains are interred in the Great Hall at Forest Lawn Glendale, having left us in 1926, one year short of being able to see our new building’s grand opening. She was 82 when she passed, sadly the victim of a fatal car crash in her commute to Whittier. Imagine this commute she did so often, just like many of us who do battle with LA traffic today, but without the benefit of freeways or great highways. And imagine if she’d lived until she actually wore herself out!

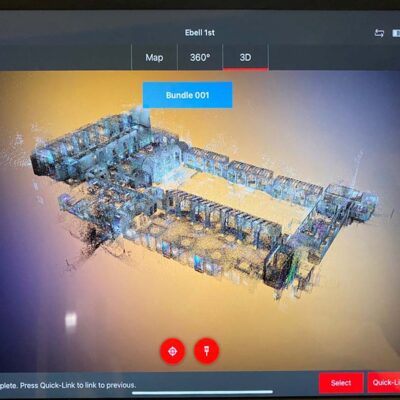

As our building centennial approaches in a few short years, think of Harriet cheering us on, letting us know we have what it takes to preserve it for the future generations, too.